A few minutes after the play begins, the actors stop, empty their pockets and repeat their last few lines. And then they do it again. And again. And again. This live approximation of a vinyl record that catches on loop goes on for a few more minutes, the actors getting slightly louder and a tinge more testy as they continue the repetition.

They can’t move, they say, as they are “waiting for Godot.” But they are actually waiting for us, the audience, to get out of our seats, walk onstage and start to piece together a puzzle out of the fragmented pieces of paper they‘ve dropped.

Cards and letters lie on the ground for audience members to discover the next clue.

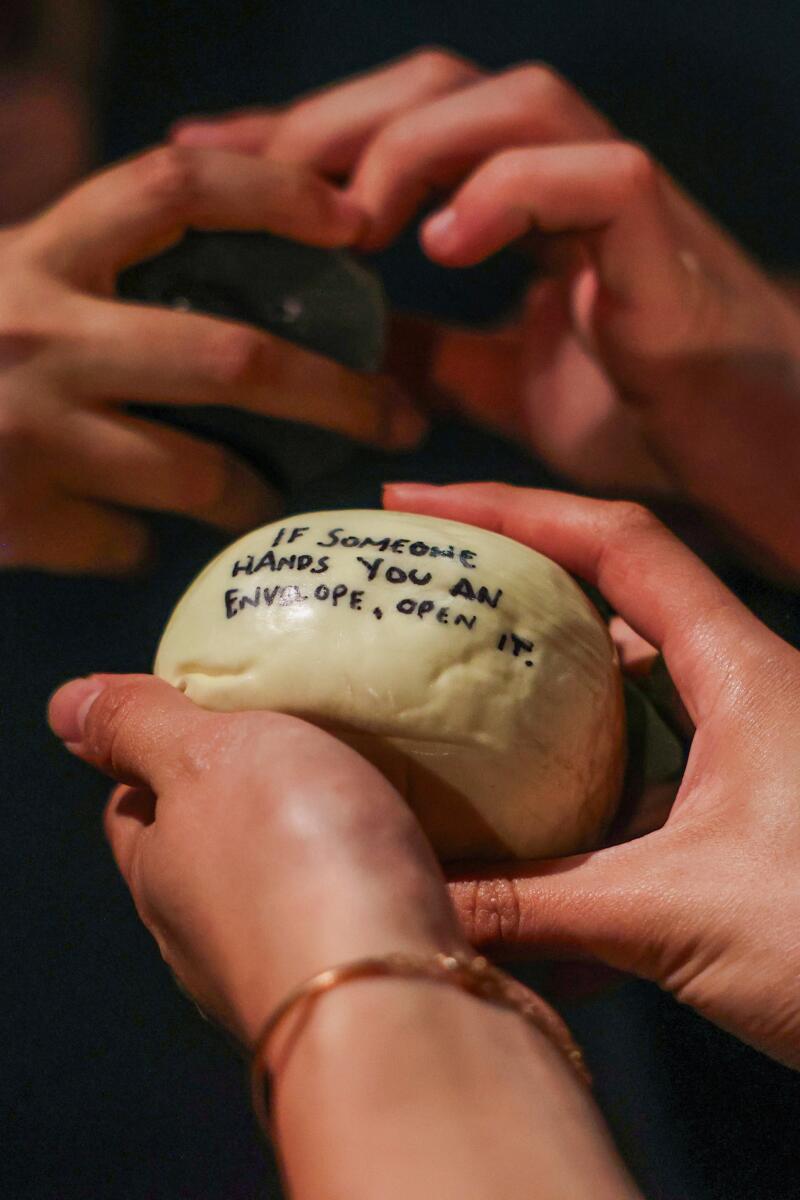

Melanie Pentecost holds a rock that gives the next context clue to to move the play forward.

This is “Escape From Godot,” an escape room that is also a work of theater — or vice versa. It upends the conventions of both. This is a play in which audience members become participants, the game requiring patrons to hop on the dials and interact with props in order to propel the narrative forward. Puzzles are hidden in the script, ensuring that the players become actors and are in abstract communication with the performers.

But its greatest trick? Inspired by Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot,” the theatrical escape room taps into the themes of the original work, creating an open-for-interpretation piece of playfully interactive art that grapples with existential questions — how we communicate, or fail to, with others, and the balance among selfish behavior, free will and empathy. Like Beckett’s play, there is no Godot who will come, but we are all caught in a world where the mundane, the absurd and our own desire for answers propel us forward.

Our group — I’m playing with seven strangers — hesitates to jump onstage and set the game afoot. It’s a break of decorum, both of theater protocol and personal boundaries. One player nervously scans his ticket, trying to find a missing clue, another flips through a notebook that was placed on her chair and most of us look at each other and whisper questions about what to do. Realizing, after about seven minutes, that there will be no end to “Escape From Godot” if we don’t move, my group begins to hesitatingly work together. In order for the actors to proceed to the next scene, we need to get them a message crafted from the ephemera that they have dropped.

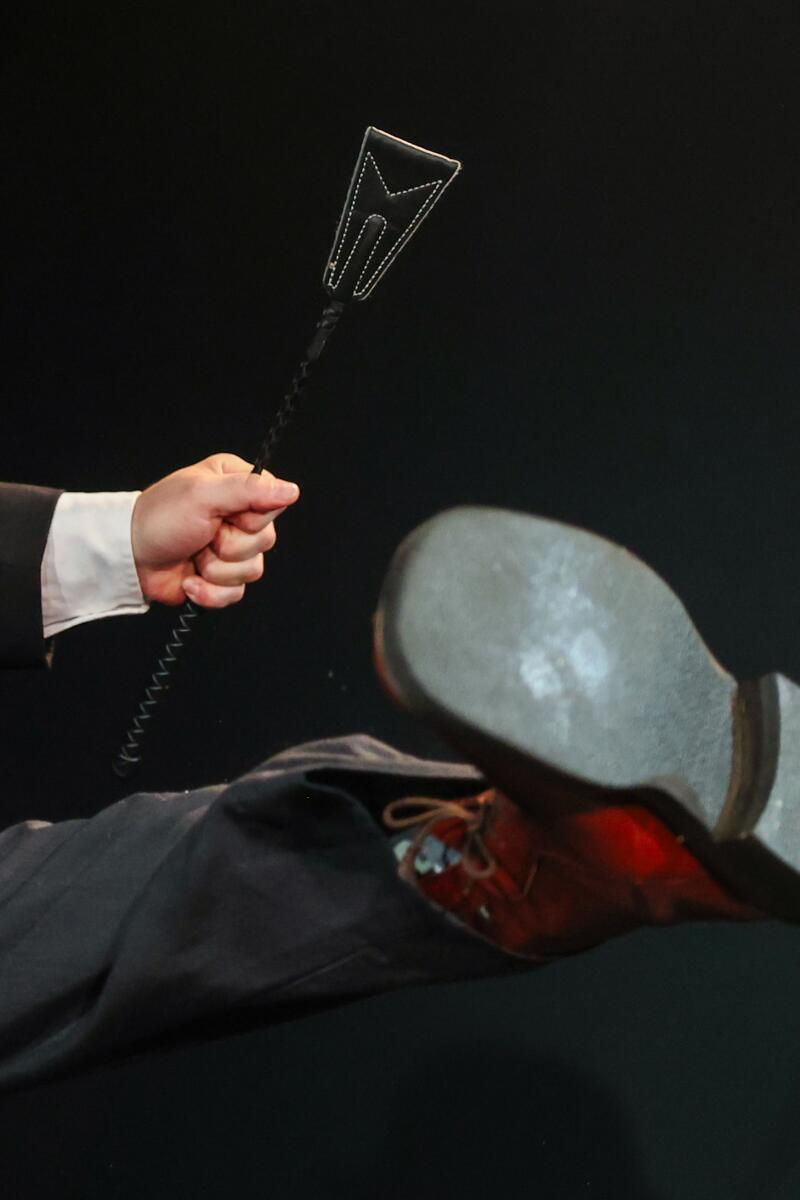

Actor Phil Daddario kicks into the air during his performance.

Daddario wipes sweat from his face while performing.

Audience members look on the ground for context clues to solve the next puzzle.

“I bet you were not the longest group that has sat,” the show’s co-creator, Jeff Crocker, later tells me when I describe those seven minutes of awkwardness. Jeff is one half of Mister & Mischief, an L.A.-based husband-and-wife duo that has crafted experiences for theme parks, zoos, museums and more. (Jeff’s wife, Andy Crocker, recently created a game-like experience for the Los Angeles Public Library system.) “Escape From Godot” is their first escape room.

“Typically, theater-minded folks, the last thing they’re ever going to do is get up onstage in the middle of the scene,” Jeff says. “That’s a hidden puzzle right there. Are you the person who is bold enough to walk onstage in the middle of a performance in order to make this repetition cease? There’s a lot of weird little social bits like that happening.”

“Escape From Godot” premiered at the Hollywood Fringe Festival in 2018 and has been periodically revived over the years, its latest as part of this month’s RECON event at the Universal City Hilton, a convention held by escape room aficionado site Room Escape Artist. An initial run through Aug. 25 at Atwater’s Moving Arts Theatre sold out, so “Escape From Godot” has been extended through Sept. 8.

The idea stemmed from Crocker hearing about an escape room in Europe that had taken place throughout a train, a promotional event tied to a film. Joking about potential properties they could base a project on, the Crockers hit on “Waiting for Godot.”

“Andy has a theater degree, and ‘Waiting for Godot’ is classically known as this play where nothing happens,” Jeff says. “To folks who don’t create theater, you hear that as the B-word, boring. It’s a go-to play where people wait for a person who never shows up. There’s more to it than that, and when you see a not-great production of ‘Waiting for Godot,’ it can feel like you want to escape. I’ve seen really great productions of it, and there’s a reason it’s a classic.”

In “Escape From Godot,” puzzles may be hidden in the bowler hats of the performers. Do we ask them to surrender their apparel or wait in the hopes that they will drop them?

Actor Mason Conrad holds a large suitcase while performing in “Escape From Godot.”

Actor Justin Okin looks through the stage play script for lines to give audience members context for the next clue.

Like Beckett’s play, characters in questionable physical shape will appear onstage, but any sense of compassion is soon overtaken by the desire to solve the next puzzle via the props they‘re carrying. Boxes and baskets with locks may be dropped onstage, their combinations found in the monologues of the actors — Justin Okin as Gigi and Bill Salyers as Dodo, stand-ins for Beckett’s Vladimir and Estragon.

“Escape From Godot” will even nod to other theatrical works. My favorite puzzle turned out to involve a combination lock affixed to a basket, in which uncovering the solution required us to listen to a monologue that alluded to famous cats in history and culture. “Escape From Godot” won’t even start unless guests solve an initial puzzle, one that necessitates we align our tickets with a theater seating chart and find the correct seat. One could opt not to play, as long as others are, and sit and watch, taking in a script that toys with our place and faith in the world, albeit with a reference to the musical “Cats.”

The longer the audience goes without hitting on the right solution, the louder and faster the monologues will become. It creates tension and tests a group to maintain a sense of calm and patience. Nothing gets too hairy; the silliness of the situation dominates the tone.

“Escape From Godot” actors applaud the audience at the end of the play, including, from left, Tiffany Ogburn, Phil Daddario, Mason Conrad, Bill Salyers and Justin Okin.

“We purely set out to fulfill our original delightful idea of having fun from escaping from a notoriously monotonous play, but in doing so, as we started to develop what the puzzles were and the way we wanted the audience to interact, it did start to support the themes of the play while also poking a little fun at it,” Jeff says. “You get the little bits of what Beckett was trying to say about what existence wants to be, what belief in God wants to be, but doing it in a way that is mischievous.”

By the time the show ends, roles have been reversed. Members of the audience have been cast as performers and the actors at times became the audience, trapped with repeating dramatic orations while watching us play. It’s a final message that isn’t too divorced from the Beckett text: We’re all performers, too often waiting for a cue.