Steve Martin had a bit of a scare this morning. It wasn’t “Saturday Night Live” producer Lorne Michaels calling to ask him to play Minnesota’s Gov. Tim Walz or anything related to his 2-year-old Nova Scotia duck tolling retriever, Sonny, who, since we last spoke, has mostly outgrown his chewing and now seems content to listen to banjo music all the livelong day.

No, the alarm had to do with Wordle, which, yes, Martin eventually solved. But it took him five tries. (I got it in six. I mean, “macaw”? Really?) Martin’s wife, Anne Stringfield, solved it in four. Martin makes a point of telling me it took him only two guesses to nail the puzzle yesterday. He’s a Wordle disciple, sometimes literally carrying the banner on top of his head.

Filmmaker Morgan Neville watched Martin solve dozens of Wordle puzzles in the many months he spent with him making the Emmy-nominated documentary “Steve! (Martin) A Documentary in 2 Pieces,” and believes they’re a key to understanding Martin’s drive.

“One thing I started to see as a pattern in his life was that he likes working on puzzles,” Neville told me over the phone. “And if you look at the things that Steve has invested himself in his life — magic, banjo, stand-up — these are things that take thousands of hours to master. And that’s what Steve likes. He likes working the problem.”

Right now, frankly, I’m trying not to be the problem Steve Martin is working. He joined me on Zoom from the exercise room in his Santa Barbara home, genial, open and keeping an ear out for Sonny.

“If you look at the things that Steve has invested himself in his life — magic, banjo, stand-up — these are things that take thousands of hours to master. And that’s what Steve likes. He likes working the problem,” says documentary director Morgan Neville.

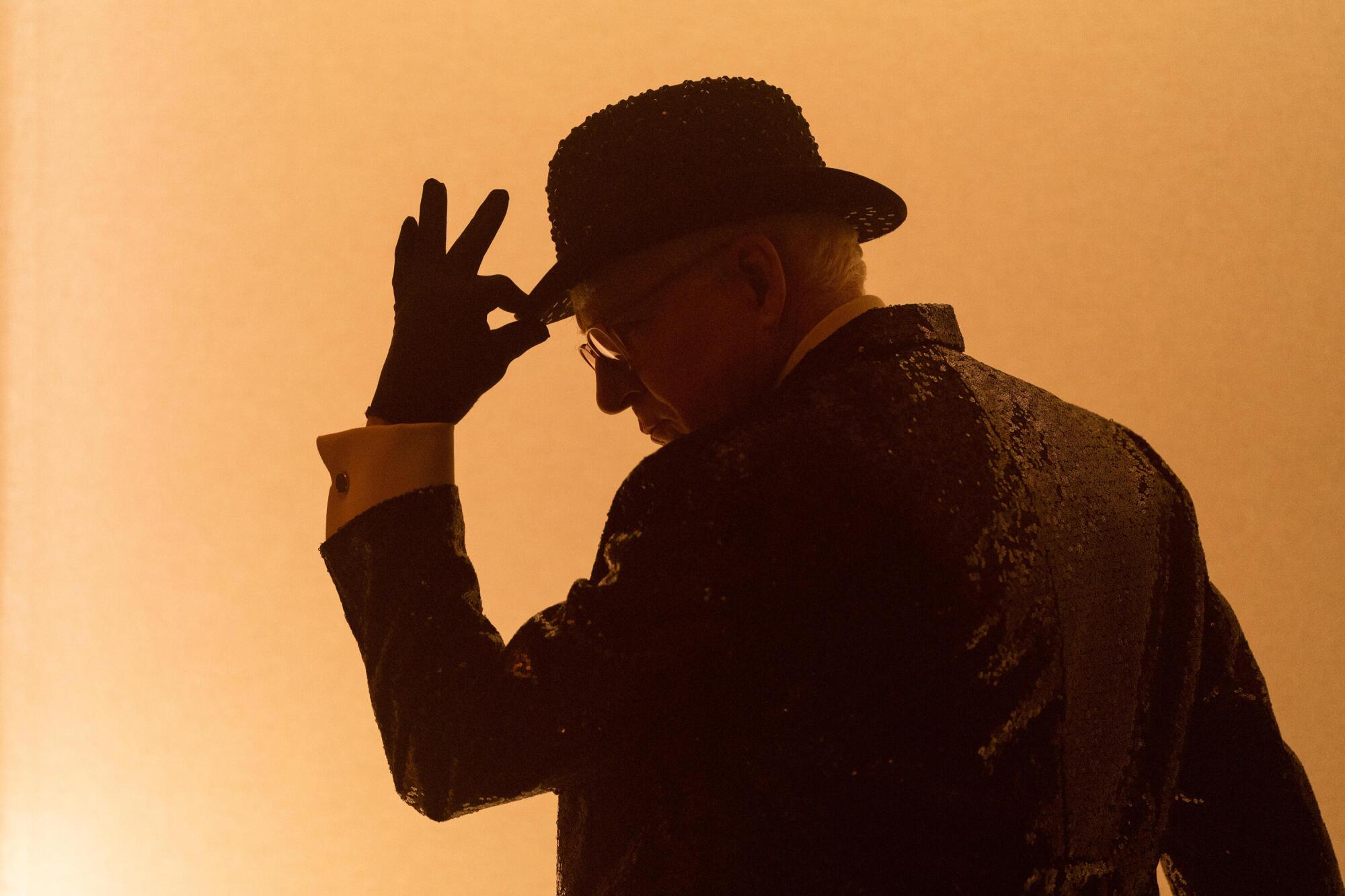

(Mark Seliger / Disney/Disney)

Morgan Neville told me about getting together with you and just talking for hours before he even began filming. Did you find all that talking about the past therapeutic?

When I finished my memoir [“Born Standing Up,” 2007], I thought, “OK. Now I never have to think about that again.” People asked me, “Why did you do this documentary?” And I go, “When else?” [Laughs]

You’re 79. If not now, when?

I was offered to do one 20 or 30 years ago, and I asked what I’d have to do. And it was three months of interviews and access to all my archives. “Gee,” I thought, “that sounds like a lot of work.” And I didn’t do it. The main reason I did it this time was that I loved Morgan’s [2018 documentary] “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” I loved how he treated Fred Rogers. He just saw him with regard and didn’t go into darkness, though I don’t know if there was any darkness there to go into.

But it still gave you a complete picture of Fred Rogers.

It ennobled him. I’m not saying that now I’m ennobled. He was kind of saint-like.

It humanized him. It detailed his struggles. I watched an interview you did about the documentary, and you were asked why the film detailed all your failures. Including them provides a complete picture.

Lorne Michaels, whom I just got off the phone with, told me years ago, he said, “I like to hire people who’ve just come off a failure because they’re very, very driven and enthusiastic.” [Laughs]

“Steve! (Martin): A Documentary in 2 Pieces” looks at Martin’s early career as well as his later life.

(Apple TV+)

Were you talking to Lorne about playing Tim Walz?

Yes. I wanted to say no and, by the way, he wanted me to say no. I said, “Lorne, I’m not an impressionist. You need someone who can really nail the guy.” I was picked because I have gray hair and glasses. And it’s ongoing. It’s not like you do it once and get applause and never do it again. Again, they need a real impressionist to do that. They’re gonna find somebody really, really good. I’d be struggling.

What did you think about writer Adam Gopnik saying in the doc, “Steve’s changed more than any person I know”?

Well, I don’t know who he knows [laughs], but I can honestly say I have changed quite dramatically from my stand-up days, which was a very isolating circumstance, combined with fame. And also a personality that was not really developed. I have changed. I can actually be fun to be with now. Whereas in the stand-up days, I deliberately wasn’t fun to be around.

Why was that?

I didn’t want to do my act in private situations or be that guy.

Everyone expected you to perform, no matter the situation?

Right. You’d go into a restaurant or even backstage at a TV show and feel that pressure of being observed. And I resisted that. But now I’m actually a real person with a wife, child and a dog and great, funny friends. The greatest thing about being a comedian is that you get to hang out with other comedians — or other artists, let’s put it that way. And I like that world.

But you’re obviously still very recognizable. What’s it like going to a restaurant now? Are you just more comfortable in your skin?

Totally. And there’s a big change that comes with age. People treat you a little differently. They’re not aggressive. If they do approach you, they’re kind.

Steve Martin as Charles-Haden Savage prepares for an upcoming musical on “Only Murders in the Building.”

(Patrick Harbron / Hulu)

Have you ever watched “Hacks”?

The first two seasons. It ended with [Jean Smart’s Deborah Vance] being bolder, taking her act out there.

And then her show kills and becomes a hit special. When she returns after it airs, the audience laughs at everything she says, no matter how innocuous. It throws her. It reminded me of what you wrote about the end of your stand-up career, how you became more of a host than a performer.

That was one word. It’s also in the best sense, not in a cynical sense, being a conductor, because you have this material you have to time. And that becomes the thrill, stitching together your act with … what do they call them? Lacuna. Those little spaces between things. When I was at my best, you’re really in charge of those little spaces.

How do you feel now when you perform with Martin Short?

Fantastic. I’ve analyzed it. It’s the utter opposite of what I used to do. What I used to do was stay away from jokes and really make it a performance. Now it’s all jokes. Not all one-liners, but routines. And it’s just really fun to do.

Did you imagine that being part of a team would make stand-up enjoyable again?

I’ve hosted the Oscars three times. The first two times, I was very nervous. But I overcame it because I’m a professional. And then the third time, I hosted with Alec Baldwin and I was not nervous at all. Looking back, I realized, “Oh, I had someone else out there with me.”

And that’s what I feel with Marty. We love to time things. We love to nail it. And we like our bits that work. Some of the jokes in our Netflix special, we thought, “Well, we have to take them out now because people have seen them.” Now, four years later, we go, “Gee, I really miss that joke.” We put it back in and nobody even remembers it.

Selena Gomez, Martin Short and Steve Martin star in “Only Murders in the Building.”

(Patrick Harbron / Hulu)

And you’ve done another season of “Only Murders in the Building” together. [The show’s fourth season premieres Aug. 27 on Hulu.] With this series, do you just take it one season at a time?

Well, yes. Because we’re not even picked up yet for another season, at least that I know of. [Laughs] But they always tease a next season in the last episode, which is a leap of faith. The show has made everyone involved with it very, very happy. And we got to shoot in L.A. this year, at Paramount, which was fun.

If you felt so comfortable hosting the Oscars for a third time with Alec Baldwin, why not make it four and host again with Marty?

That represents so much work for us. And we love our summers. When I hosted before, I started working months ahead of time. And now I have a completely different life. I’m not as free. It’s a lot of work and we’re working.

So that would be a no.

[Laughs] Yeah. I have a joke for the Oscars that I never used. But I always think it’s funny. I’ll come out and say, “I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking, ‘Steve, how did you get to host the Oscars?’ It was easy. I just called my agent and I said, ‘Get me something thankless.’”

That seems to be the prevailing consensus right now. The motion picture academy has had trouble finding a host.

They don’t pay, either. The Golden Globes pay, so they get Tina Fey and Amy [Poehler]. And Ricky Gervais. The Oscars should pay. When you consider the amount of work, it’s at least several months of mental churning.

You’d need to start tomorrow.

Yesterday. Oh, and one last thing: They have not asked. [Laughs]

You talk about rummaging through boxes of memorabilia for the documentary and coming to the conclusion that I think a lot of us arrived at over the years: I’ve saved all the wrong things.

I saved things related to my career when I should have saved things related to people. Photographs. Of course, we didn’t have access to cameras then like we do now. It was rare. And if someone took your photo, it was a huge process to get a copy.

But you know, you save your picture on a magazine that’s completely meaningless. Michael Caine told me, “I realized who was making money in Hollywood. I’d go to actors’ homes, and they’d have pictures of themselves on the wall. And I go to producers’ homes that have Van Goghs and Monets.”

It feels like you made a shift, though, applying your work ethic to relationships in your life, particularly your parents.

That started with a friend whose mother committed suicide and father got hit by a car. He said, “If you have any resolution to achieve with your parents, do it now.” And I thought that was good advice because I had almost no rapport.

So you started taking your parents to lunch every weekend for 15 years …

And it was one of the best things I ever did, though I realized when I take them both out, they each would misremember things and then end up correcting each other. So I’d take one out on one Sunday and the other one on the next Sunday. So they’d be alone and I could get information. [Laughs]

Steve Martin spent many months with filmmaker Morgan Neville shooting the documentary.

(Apple TV+)

You said you needed to make 40 movies to get five good ones. What five stand out?

Oh, I’d say “Father of the Bride,” “Planes, Trains and Automobiles,” “Roxanne.” I like “Bowfinger.” “The Jerk.” I love all the movies I made with Frank Oz — “Dirty Rotten Scoundrels,” “Little Shop [of Horrors]” and “Housesitter.”

What about “L.A. Story”?

I just don’t know what to make of “L.A. Story.” Because it’s … um … [Long pause] I let other people decide.

I’ve never heard you at a loss of what to make of your other movies. Why does “L.A. Story” baffle you?

It’s very personal. It’s not story-driven. It’s funny … Hauser & Wirth, the gallery in Los Angeles, is doing a show starting in September based around “L.A. Story.” They’ve got all these artists that quite liberally fit into the concept of L.A. And they’re doing a good job of it.

The movie certainly saw L.A. in a more positive light than, say, “Annie Hall.” It felt like it came from someone who loved the city.

I’ve always loved Los Angeles. My initial concept of it was a love story set in L.A. I knew that the city would take on a character. And I had the idea of the talking traffic signs. I wanted it to be magical, and I’m just not sure if I achieved that. But the city is better. When I left in the ’70s, the sky was green. The traffic hasn’t changed. But at least the sky is clear now. [Laughs]